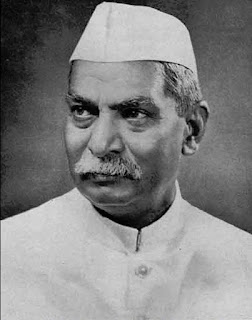

concluding remarks by The Honourable Dr. Rajendra Prasad on Constitution of India Saturday, the 26th November,1949

concluding remarks by The Honourable

Dr. Rajendra Prasad on Constitution of India

Saturday, the 26th November,1949

Mr.

President: .....

Before I do

that, I would like to mention some facts which will show the tremendousness of

the task which we undertook some three years ago. If you consider the

population with which the Assembly has had to deal, you will find that it is

more than the population of the whole of Europe minus Russia, being 319

millions as against 317 millions. The countries of Europe have never beenable

to join together or coalesce even in a Confederacy, much less under one unitary

Government. Here, in spite of the size of the population and the country, we

have succeeded in framing a Constitution which covers the whole of it. Apart

from the size, there were other difficulties which were inherent in the problem

itself. We have got many communities

living in this country. We have got many

languages prevalent in different

parts of it. We have got other kinds of differences dividing the people in the different parts from one

another. We had to make provision not only for areas which are advanced educationally

and economically; we had also to make provision for backward people like the Tribes and for backward areas like the

Tribal areas. The communal problem had been one of the knottiest problems which

the country has had before it for a pretty long time. The Second RoundTable Conference

which was attended by Mahatma Gandhi

failed because the communal problem could not be solved. The subsequent history

of the country is too recent to require narration here; but we know this that

as a result, the country has had to be divided and we have lost two big

portions in the north-east and north-west.

Another

problem of great magnitude was the problem of the Indian States. When the British came to India, they did

not conquer the country as a whole or at one stroke. They got bits of it

from time to time. The bits which came into their direct possession and control

came to be known as British India; but a considerable portion remained under

the rule and control of the Indian Princes. The British thought at the time

that it was not necessary or profitable for them to take direct control of

those territories, and they allowed the old Rulers to continue subject to their

suzerainty. But they enteredinto

various kinds of treaties and engagements with them. We had something near six

hundred States covering more than one-third of the territory of India and

one-fourth of the population of the country. They varied in size from small

tiny principalities to big States like Mysore, Hyderabad, Kashmir, etc. When

the British decided to leave this country, they transferred power to us; but at

the same time, they also declared that all the treaties and engagements they

had with the Princes had lapsed. The aramountcy

which they had so long exercised and by which they could keep the Princes in

order also lapsed. The Indian Government was them faced with the problem of

tackling these States which had different traditions of rule, some of them

having some form of popular representation in Assembliesand some having no

semblance of anything like that, and governing completely autocratically. As a

result of the declaration that the treaties with the Princes and Paramountcy

had lapsed, itbecame open to any Prince or any combination of Princes to assume

independence and even to enter into negotiations with any foreign power and

thus become islands of independent territory within the

country. There

were undoubtedly geographical and other compulsions which made it physically

impossible for

most of them to go against the Government of India but constitutionally it had

become

possible. The

Constituent Assembly therefore had at the very beginning of its labours, to

enter into

negotiations

with them to bring their representatives into the Assembly so that a

constitution might

be framed in

consultation with them. The first efforts were successful and some of them did

join this Assembly at an early stage but others hesitated. It is not necessary

to pry into the secrets of what was happening in those days behind the scenes.

It will be sufficient to state that by August 1947 when the Indian Independence

Act came into force, almost all of them with two notable exceptions, Kashmir in

the north and Hyderabad in the South, had acceded to India. Kashmir soon after followed the example of others and acceded.

There were standstill agreements with all of them including Hyderabad which continued the status

quo. As time passed, it became apparent that it was not possible at

any rate for the smaller States to maintain their separate independence

existence and then a process of

integration with India started. In course of time not only have all the smaller

States coalesced and become integrated with some province or other of India but

some of the larger ones also have joined. Many of the States have formed Unions

of their own and such Unions have become part of the Indian Union. It must be

said to the credit of the Princes and the people of the States no less than to

the credit of the States Ministry under the wise and far-sighted guidance of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel that by the

time we have been able to pass this Constitution, the States are now

more or less

in the same position as the Provinces and it has become possible to describe

all of them

including the

Indian States and the Provinces as States in the Constitution. The announcement

which

has been made

just now by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel makes the position very clear, and now

there is

no difference

between the States, as understood before, and the provinces in the New

Constitution.

It has

undoubtedly taken us three years to complete this work, but when we consider

the work

that has been

accomplished and the number of days that we have spent in framing this

Constitution, the details of which were given by the Honourable Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, yesterday, we have

no reason to be sorry for the time spent.

It has

enabled the apparently intractable problem of the States and the communal

problem to be

solved. What

had proved insoluble at the Round Table Conference and had resulted in the

division of the country has been solved with the consent of all parties

concerned, and again under the wise

guidance of

Honourable Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

At first we

were able to get rid of separate electorates which had poisoned our political

life for so

many years,

but reservation of seats for the communities which enjoyed separate electorates

before had to be conceded, although on the basis of their population and not as

had been done in the Act of 1919 and the

Act of 1935 of giving additional representation on account of the so-called

historical and other superiority claimed

by some of the communities. It has become possible only because the Constitution was not passed earlier that even

reservation of seats has been given up by the

communities concerned and so our Constitution does not provide for

reservation of seats on

communal

basis, but for reservation only in favour of two classes of people in our

population, namely, the depressed classes who are Hindus and the tribal people,

on account of their backwardness ineducation and in other respects. I therefore

see no reason to be apologetic about the

delay. The cost too which the Assembly has had to incur during its three

year's existence is not too high when you take into consideration the factors

going to constitute it. I understand that the expenses up to the 22nd of

November come to Rs. 63,96,729/-.

The method

which the Constituent Assembly adopted in connection with the Constitution was

first

to lay down

its ‘terms of reference’ as it were in the form of an Objective Resolution which was moved

by Pandit

Jawaharlal Nehru in as inspiring speech and which constitutes now the Preamble

to our

Constitution.

It then proceeded to appoint a number of committees to deal with different

aspects of

the

Constitutional problem. Dr. Ambedkar mentioned the names of these Committees.

Several of

these had as

their Chairman either Pandit Jawaharlal

Nehru or Sardar Patel to whom thus goes the

credit for

the fundamentals of our Constitution. I have only to add that they all worked

in a businesslike

manner and

produced reports which were considered by the Assembly and their

recommendations

were adopted as the basis on which the draft of the Constitution had to be

prepared.

This was done by Mr. B. N. Rau, who

brought to bear on his task a detailed knowledge of

Constitutions

of other countries and an extensive knowledge of the conditions of this country

as well

as his own

administrative experience. The Assembly then appointed the Drafting Committee

which

worked on the

original draft prepared by Mr. B. N. Rau and produced the Draft Constitution

which was

considered by

the Assembly at great length at the second reading stage. As Dr. Ambedkar

pointed

out, there

were not less than 7,635 amendments of

which 2,473 amendments were moved. I am

mentioning

this only to show that it was not only the Members of the Drafting Committee

who were

giving their

close attention to the Constitution, but other Members were vigilant and

scrutinizing the

Draft in all

its details. No wonder, that we had to consider not only each article in the

Draft, but

practically

every sentence and sometimes, every word in every article. It may interest

honourable

members to

know that the public were taking great interest in its proceedings and I have

discovered

that no less

than 53,000 visitors were admitted

to the Visitors gallery during the period when the

Constitution

has been under consideration. In the result, the Draft Constitution has

increased in size,

and by the

time it has been passed, it has come to have 395 articles and 8 schedules, instead

of the

243 articles

and 13 schedules of the original Draft of Mr. B. N. Rau. I do not attach much

importance

to the

complaint which is sometimes made that it has become too bulky. If the

provisions have been

well thought

out, the bulk need not disturb the equanimity of our mind.

We have now to consider the salient

features of the Constitution. The first question which arises

and which has

been mooted is as to the category to

which this Constitution belongs. Personally, I do

not attach

any importance to the label which may be attached to it – whether you call it

Federal

Constitution

or Unitary Constitution or by any other name. It makes no difference so long as

the

Constitution

serves our purpose. We are not bound to have a constitution which completely

and fully

falls in line

with known categories of constitutions in the world. We have to take certain

facts of

history in

our own country and the Constitution has not to an inconsiderable extent been

influenced

by such

realities as facts of history.

You are all

aware that until the Round Table conference of 1930, India was completely a

Unitary

Government,

and the provinces derived whatever power they possessed from the Government of

India. It was

there for the first time that the question of Federation in a practical form

arose which

would include

not only the provinces but also the many States that were in existence. The

Constitution

of 1935 provided for a Federation in which both the provinces of India and the

States

were asked to

join. But the federal part of it could not be brought into operation, because

terms on

which the

Princes could agree to join it could not be in settled in spite of prolonged

negotiation. And,

when the war

broke out, that part of the Constitution had practically to be abrogated.

In the

present Constitution it has been possible not only to bring in practically all

the States which

fell within

our geographical limits, but to integrate the largest majority of them in

India, and the

Constitution

as it stands practically makes no difference so far as the administration and

the

distribution

of powers among the various organs of the State are concerned between what were

the

Provinces and

what were Indian States before. They are all now more or less on the same

footing

and, as time passes,

whatever little distinction still exists is bound to disappear. Therefore, so

far as

labelling is

concerned, we need not be troubled by it.

Well, the

first and the most obvious fact which will attract any observer is the fact

that we are

going to have

a Republic. India knew republics in

the past olden days, but that was 2,000 years ago

or more and

those republics were small republics. We never had anything like the Republic

which we

are going to

have now, although there were empires in those days as well as during the

Mughal

period which

covered very large parts of the country. The President of the Republic will be

an elected

President. We

never have had an elected Head of the State which covered such a large area of

India.

And it is for

the first time that it becomes open to the humblest and the lowliest citizens

of the

country to

deserve and become the President or the Head of this big State which counts

among the

biggest

States of the world today. This is not a small matter. But because we have an

elected

President,

some of the problems which are of a very difficult nature have arisen. We have

provided

for the

election of the President. We have provided for an elected legislature which is

going to have

supreme

authority. In America, the legislature and the President are both elected and,

there both

have more or

less equal powers – each in its or his own sphere, the President in the

executive sphere

and the

legislature in the legislative sphere.

We considered

whether we should adopt the American model or the British model where we have

a hereditary

king who is the fountain of all honour and power, but who does not actually

enjoy any

power. All

the power rests in the Legislature to which the Ministers are responsible. We

have had to

reconcile the

position of an elected President with an elected Legislature and, in doing so,

we have

adopted more

or less the position of the British Monarch for the President. This may or may

not be

satisfactory.

Some people think too much power has been given to the President; others think

that

the

President, being an elected President, should have even more powers than are

given to him.

If you look

at it from the point of view of the electorate which elects the Parliament and

which

elects the

President, you will find that practically the entire adult population of the

country joins in

electing this

Parliament and it is not only the Members of the Parliament of India but also

the

Members of

the Legislative Assemblies of the States who join in electing the President. It

thus comes

about that,

while the Parliament and Legislative Assemblies are elected by the adult

population of the

country as a

whole, the President is elected by representatives who represent the entire

population

twice over, once

as representatives of the States and again as their representatives in the

Central

Parliament of

the country. But although the President is elected by the same electorate as

the Central

and State

Legislatures, it is as well that his position is that of a Constitutional

President.

Then we come

to the Ministers. They are of course responsible to the Legislature and tender

advice to the

President who is bound to act according to that advice. Although there are no

specific

provisions,

so far as I know, in the Constitution itself making it binding on the President

to accept the

advice of his

Ministers, it is hoped that the convention under which in England the King acts

always on

the advice of

his Ministers will be established in this country also and, the president, not

so much on

account of

the written word in the Constitution, but as the result of this very healthy

convention, will

become a

Constitutional President in all matters.

The Central Legislature consists of two

Houses known as the House of People and the Council of

States which both together constitute the

Parliament of India. In the Provinces, or States as they are

now called,

we shall have a Legislative Assembly in all of them except those which are

mentioned in

Parts C and D

of Schedule I, but every one of them will not have a Second Chamber. Some of

the

provinces,

whose representatives felt that a Second Chamber is required for them, have

been

provided with

a Second Chamber. But there is a provision in the Constitution that if a

province does

not want such

a Second Chamber to continue or if a province which has not got one wants to

establish

one, the wish has to be expressed through the Legislature by a majority of

two-thirds of the

Members

voting and by a majority of the total number of Members in the Legislative

Assembly. So,

even while

providing some of the States with Second Chambers, we have provided also for

their easy

removal or

for their easy establishment by making this kind of amendment of the

Constitution not a

Constitutional

Amendment, but a matter of ordinary parliamentary legislation.

We have

provided for adult suffrage by which

the legislative assemblies in the provinces and the

House of the

People in the Centre will be elected. It is a very big step that we have taken.

It is big not

only because

our present electorate is a very much smaller electorate and based very largely

on

property

qualification, but it is also big because it involves tremendous numbers. Our

population now

is something

like 320 millions if not more and we have found from experience gained during

the

enrolment of

voters that has been going on in the provinces that 50 per cent. roughly

representing

the adult

population. And on that basis we shall have not less than 160 million voters on

our rolls. The

work of organising

election by such vast numbers is of tremendous magnitude and there is no other

country where

election on such a large scale has ever yet been held.

I will just

mention to you some facts in this connection. The legislative assemblies in the

provinces, it

is roughly calculated, will have more than 3,800 members who will have to be

elected in

as many

constituencies or perhaps a few less. Then there will be something like 500

members for the

House of the

People and about 220 Members for the Council of States. We shall thus have to

provide

for the

election of more than 4,500 members and the country will have to be divided

into something

like 4,000

constituencies or so. I was the other day, as a matter of amusement,

calculating what our

electoral

roll will look like. If you print 40 names on a page of foolscap size, we shall

require

something

like 20 lakhs of sheets of foolscap size to print all the names of the voters,

and if you

combine the

whole thing in one volume, the thickness of the volume will be something like

200 yards.

That alone

gives us some idea of the vastness of the task and the work involved in

finalising the rolls,

delimiting

Constituencies, fixing polling stations and making other arrangements which

will have to be

done between

now and the winter of 1950-51 when it is hoped the elections may be held.

Some people

have doubted the wisdom of adult franchise. Personally, although I look upon it

as

an experiment

the result of which no one will be able to forecast today, I am not dismayed by

it. I am

a man of the

village and although I have had to live in cities for a pretty long time, on

account of my

work, my

roots are still there. I, therefore, know the village people who will

constitute the bulk of this

vast

electorate. In my opinion, our people possess intelligence and commonsense.

They also have a

culture which

the sophisticated people of today many not appreciate, but which is solid. They

are not

literate and

do not possess the mechanical skill of reading and writing. But, I have no

doubt in my

mind that

they are able to take measure of their own interest and also of the interests

of the country

at large if

things are explained to them. In fact, in some respects, I consider them to be

even more

intelligent than

many a worker in a factory, who loses his individuality and becomes more or

less a

part of the

machine which he has to work. I have, therefore, no doubt in my mind that if

things are

explained to

them, they will not only be able to pick up the technique of election, but will

be able to

cast their

votes in an intelligent manner and I have, therefore, no misgivings about the

future, on

their

account. I cannot say the same thing about the other people who may try to

influence them by

slogans and

by placing before them beautiful pictures of impracticable programmes.

Nevertheless, I

think their

sturdy commonsense will enable them to see things in the right perspective. We

can,

therefore,

reasonably hope that we shall have legislatures composed of members who shall

have their

feet on the

ground and who will take a realistic view of things.

Although

provision has been made for a second

chamber in the Parliament and for second

chambers in some of the States, it is the

popular House which is supreme. In all financial and money

matters, the

supremacy of the popular House is laid down in so many words. But even in

regard to

other matters

where the Upper Chamber may be said to have equal powers for initiating and

passing

laws, the

supremacy of the popular House is assured. So far as Parliament is concerned,

if a

difference

arises between the two Chambers, a joint session may be held; but the

Constitution

provides that

the number of Members of the Council of States shall not be more than 50

percent. of

the Members

of the House of the People. Therefore, even in the case of a joint session, the

supremacy of

the House of the People is maintained, unless the majority in that very House

is a small

one which

will be just a case in which its supremacy should not prevail. In the case of

provincial

legislatures,

the decision of the Lower House, prevails if it is taken a second time. The

Upper Chamber

therefore can

only delay the passage of Bills for a time, but cannot prevent it. The

President or the

Governor, as

the case may be, will have to give his assent to any legislation, but that will

be only on

the advice of

his Ministry which is responsible ultimately to the popular House. Thus, it is

the will of

the people as

expressed by their representatives in the popular Chamber that will finally

determine all

matters. The

second Chamber and the President or the Governor can only direct

reconsideration and

can only

cause some delay; but if the popular Chamber is determined, it will have its

way under the

Constitution.

The Government therefore of the country as a whole, both in the Centre and in

the

Provinces,

will rest on the will of the people which will be expressed from day to day

through their

representatives

in the legislatures and, occasionally directly by them at the time of the

general

elections.

We have

provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is

difficult to

suggest

anything more to make the Supreme Court

and the High Courts independent of the influence

of the Executive. There is an attempt

made in the Constitution to make even the lower judiciary

independent

of any outside or extraneous influence. One of our articles makes it easy for

the State

Governments

to introduce separation of Executive from Judicial functions and placing the

magistracy

which deals

with criminal cases on similar footing as Civil Courts. I can only express the

hope that this

long overdue

reform will soon be introduced in the States.

Our

Constitution has devised certain independent agencies to deal with particular

matters. Thus, it

has provided

for Public Service Commission both

for the Union and for the States and placed such

Commission on

an independent footing so that they may discharge their duties without being

influenced by

the Executive. One of the things against which we have to guard is that there

should be

no room as

far as it is humanly possible for jobbery, nepotism and favouritism. I think

the provisions

which we have

introduced into our Constitution will be very helpful in this direction.

Another

independent authority is the Comptroller and Auditor-General who will watch our

finances

and see to it

that no part of the revenues of India or of any of the States is used for

purposes and on

items without

due authority and whose duty it will be otherwise to keep our accounts in

order. When

we consider

that our Governments will have to deal with hundreds of crores, it becomes

clear how

important and

vital this Department will be. We have provided another important authority,

i.e., the

Election

Commissioner whose function it will be to conduct and supervise the elections

to the

Legislatures

and to take all other necessary action and connection with them. One of the

dangers

which we have

to face arises out of any corruption which parties, candidates or the Government

in

power may

practise. We have had no experience of democratic elections for a long time

except during

the last few

years and now that we have got real power, the danger of corruption is not only

imaginary. It

is therefore as well that our Constitution guards against this danger and makes

provision for

an honest and straightforward election by the voters. In the case of the Legislature, the

High Courts, the Public Services

Commission, the Comptroller and Auditor-General and the Election

Commissioner, the Staff which will assist

them in their work has also been placed under their control

and in most of these cases their

appointment, promotion and discipline vest in the particular

institution to which they belong thus

giving additional safeguards about their independence.

The

Constitution has given in two Schedules, namely Schedules V and VI, special provisions for

administration

and control of Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes. In the case of the Tribes

and

Tribal Areas

in States other than Assam, the Tribes will be able to influence the

administration

through the

Tribes Advisory Council. In the case of the Tribes and Tribal Areas in Assam,

they are

given larger

powers through their district Councils and Autonomous Regional Councils. There

is,

further provision

for a Minister in the State Ministries to be in charge of the welfare of the

Tribes and

the Scheduled

Castes and a Commission will also report about the way in which the areas are

administered.

It was necessary to make this provision on account of the backwardness of the

Tribes

which require

protection and also because their own way of solving their own problems and

carrying

on their

Tribal life. These provisions have given them considerable satisfaction as the

provision for the

welfare and

protection of the Scheduled Castes has given satisfaction to them.

The

Constitution has gone into great details regarding the distribution of power and functions

between the Union and the States in all

aspects of their administrative and other activities. It has

been said by

some that the powers given to the Centre are too many and too extensive and the

States have

been deprived of power which should really belong to them in their own fields.

I do not

wish to pass

any judgment on this criticism and can only say that we cannot be too cautious

about

our future,

particularly when we remember the history of this country extending over many

centuries.

But such

powers as have been given to the Centre to act within the sphere of the States

relate only to

emergencies,

whether political or financial and economic, and I do not anticipate that there

will be

any tendency

on the part of the Centre to grab more power than is necessary for good

administration

of the

country as a whole. In any case the Central Legislature consists of

representatives from the

States and

unless they are convinced of their over-riding necessity, they are not likely

to consent to

the use of

any such powers by the Central executive as against the States whose people

they

represent. I

do not attach much importance to the complaint that residuary powers have been

vested

in the Union.

Powers have been very meticulously and elaborately defined and demarcated in

the

three lists

of Schedule Seven, and the residue whatever it may be, is not likely to cover

any large

field, and,

therefore, the vesting of such residuary powers does not mean any very serious

derogation

in fact from

the power which ought to belong to the States.

One of the

problems which the Constituent Assembly

took considerable time in solving relates to

the language for official purposes of the

country. There is a natural desire that the we should have

our own

language, and in spite the difficulties on account of the multiplicity of

languages prevalent in

the country,

we have been able to adopt Hindi which is the language that is understood by

the largest

number of

people in the country as our official language. I look upon this as a decision

of very great

importance

when we consider that in a small country like Switzerland they have no less than three

official languages and in South Africa two

official languages. It shows a spirit of accommodation and a

determination

to organize the country as one nation that those whose language is not Hindi

have

voluntarily

accepted it as the official language. (Cheers). There is no question of

imposition now.

English

during the period of British rule, Persian during the period of the Muslim

Empire were Court

and official

languages. Although people have studies them and have acquired proficiency in

them,

nobody can

claim that they were voluntarily adopted by the people of the country at large.

Now for

the first

time in our history we have accepted one language which will be the language to

be used all

over the

country for all official purposes, and let me hope that it will develop into a

national language

in which all

will feel equal pride while each area will be not only free, but also

encouraged to develop

its own

peculiar language in which its culture and its traditions are enshrined. The

use of English

during the

period of transition was considered inevitable for practical reasons and no one

need be

despondent

over this decision, which has been dictated purely by practical considerations.

It is the

duty of the

country as a whole now and especially of those whose language is Hindi to so

shape and

develop it as

to make it the language in which the composite culture of India can find its

expression

adequately

and nobly.

Another

important feature of our Constitution is that it enables amendments to be made without

much difficulty. Even the

constitutional amendments are not as difficult as in the case of some other

countries,

but many of the provisions in the Constitution are capable of being amended by

the

Parliament by

ordinary acts and do not require the procedure laid down for constitutional

amendments to

be followed. There was a provision at one time which proposed that amendments

should be

made easy for the first five years after the Constitution comes into force, but

such a

provision has

become unnecessary on account of the numerous exceptions which have been made

in

the

Constitution itself for amendments without the procedure laid down for

constitutional

amendments.

On the whole, therefore, we have been able to draft a Constitution which I

trust will

serve the

country well.

There is a special provision in our

Directive Principles to which I attach great importance. We have

not provided

for the good of our people only but have laid down in our directive principles

that our

State shall

endeavour to promote material peace and security, maintain just and honourable

relations

between

nations, foster respects for international law and treaty obligations and

encourage

settlement of

international disputes by arbitration. In a world torn with conflicts, in a

world which

even after

the devastation of two world wars is still depending on armaments to establish

peace and

goodwill, we

are destined to play a great part, if we prove true to the teachings of the

Father of the

Nation and

give effect to this directive principle in our Constitution. Would to God that

he would give

us the wisdom

and the strength to pursuance this path in spite of the difficulties which

beset us and

the atmosphere

which may well choke us. Let us have faith in ourselves and in the teachings of

the

Master whose

portrait hangs over my head and we shall fulfil the hopes and prove true to the

best

interests of

not only our country but of the world at large.

I do not

propose to deal with the criticism which relate mostly to the articles in the

part dealing

with Fundamental Rights by which absolute rights

are curtailed and the articles dealing with

Emergency Powers. Other Members have

dealt with these objections at great length. All that I need

state at this

stage is that the present conditions of the country and tendencies which are

apparent

have

necessitated these provisions which are also based on the experience of other

countries which

have had to

enforce them through judicial decisions, even when they were not provided for

in the

Constitution.

There are only two regrets which I must

share with the honourable Members I would have liked to

have some qualifications laid down for members of the

Legislatures. It is anomalous that we should

insist upon

high qualifications for those who administer or help in administering the law

but none for

those who

made it except that they are elected. A law giver requires intellectual

equipment but even

more than

that capacity to take a balanced view of things to act independently and above

all to be

true to those

fundamental things of life – in one word – to have character (Hear,

hear). It is not

possible to

devise any yardstick for measuring the moral qualities of a man and so long as

that is not

possible, our

Constitution will remain defective. The

other regret is that we have not been able to

draw up our first Constitution of a free

Bharat in an Indian language. The difficulties in both cases

were

practical and proved insurmountable. But that does not make the regret any the

less poignant.

We have

prepared a democratic Constitution. But successful working of democratic

institutions

requires in

those who have to work them willingness to respect the view points of others,

capacity for

compromise

and accommodation. Many things which cannot be written in a Constitution are

done by

conventions.

Let me hope that we shall show those capacities and develop those conventions.

The

way in which

we have been able to draw this Constitution without taking recourse to voting

and to

divisions in

Lobbies strengthens that hope.

Whatever the Constitution may or may not

provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon

the way in which the country is

administered. That will depend upon the men who administer it. It is a

trite saying

that a country can have only the Government it deserves. Our Constitution has

provision

in it which

appear to some to be objectionable from one point or another. We must admit

that the

defects are

inherent in the situation in the country and the people at large. If the people

who are

elected are

capable and men of character and integrity, they would be able to make the best

even of

a defective

Constitution. If they are lacking in these, the Constitution cannot help the

country. After

all, a

Constitution like a machine is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of

the men who control it

and operate

it, and India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have

the

interest of

the country before them. There is a fissiparous tendency arising out of various

elements in

our life. We

have communal differences, caste differences, language differences, provincial

differences

and so forth. It requires men of strong character,

men of vision, men who will not sacrifice the

interests of the country at large for the

sake of smaller groups and areas and who will rise over the

prejudices which are born of these

differences. We can only hope

that the country will throw up such

men in abundance. I can say this from

the experience of the struggle that we have had during the

period of the

freedom movement that new occasions throw up new men; not once but almost on

every

occasion when all leading men in the Congress were clapped into prison suddenly

without

having the

time to leave instructions to others and even to make plans for carrying on

their

campaigns,

people arose from amongst the masses who were able to continue and conduct the

campaigns

with intelligence, with initiative, with capacity for organization which nobody

suspected

they

possessed. I have no doubt that when the country needs men of character, they

will be coming

up and the

masses will throw them up. Let not those who have served in the past therefore

rest on

their oars,

saying that they have done their part and now has come the time for them to

enjoy the

fruits of

their labours. No such time comes to anyone who is really earnest about his

work. In India

today I feel

that the work that confronts us is even more difficult than the work which we

had when

we were

engaged in the struggle. We did not have then any conflicting claims to

reconcile, no loaves

and fishes to

distribute, no powers to share. We have all these now, and the temptations are

really

great. Would

to God that we shall have the wisdom and the strength to rise above them, and

to serve

the country

which we have succeeded in liberating.

Mahatma

Gandhi laid stress on the purity of the

methods which had to be pursued for attaining

our ends. Let us not forget that this

teaching has eternal value and was not intended only for the

period of

stress and struggle but has as much authority and value today as it ever had

before. We

have a

tendency to blame others for everything that goes wrong and not to introspect

and try to see

if we have

any share in it or not. It is very much easier to scan one's own actions and

motives if one

is inclined

to do so than to appraise correctly the actions and motives of others. I shall

only hope that

all those

whose good fortune it may be to work this Constitution in future will remember

that it was a

unique

victory which we achieved by the unique method taught to us by the Father of

the Nation, and

it is up to

us to preserve and protect the independence that we have won and to make it

really bear

fruit for the

man in the street. Let us launch on this new enterprise of running our

Independent

Republic with

confidence, with truth and non-violence and above all with heart within and God

over

head.

Before I

close, I must express my thanks to all the Members of this august Assembly from

whom I

have received

not only courtesy but, if I may say so, also their respect and affection.

Sitting in the

Chair and

watching the proceedings from day to day. I have realised as nobody else could have,

with

what zeal and

devotion the members of the Drafting Committee and especially its Chairman, Dr.

Ambedkar in

spite of his indifferent health, have worked. (Cheers). We could never make a

decision

which was or

could be ever so right as when we put him on the Drafting Committee and made

him its

Chairman. He

has not only justified his selection but has added luster to the work which he

has done.

In this

connection, it would be invidious to make any distinction as among the other

members of the

Committee. I

know they have all worked with the same zeal and devotion as its Chairman, and

they

deserve the

thanks of the country.

I must

convey, if you will permit me, my own thanks as well as the thanks of the house

to our

Constitutional

Adviser, Shri B. N. Rau, who worked honorarily all the time that he was here,

assisting

the Assembly

not only with his knowledge and erudition but also enabled the other Members to

perform their

duties with thoroughness and intelligence by supplying them with the material

on which

they could

work. In this he was assisted by his band and research workers and other

members of the

staff who

worked with zeal and devotion. Tribute has been paid justly to Shri S. N.

Mukerjee who has

proved of

such invaluable help to the Drafting Committee.

Coming to the

staff of the Secretariat of the Constituent Assembly I must first mention and

thank

the

Secretary, Mr. H. V. R. Yengar, who organised the Secretariat as an efficient

working body.

Although

latterly when the work began to proceed with more or less clock-work

regularity, it was

possible for

us to relieve him of part of his duties to take up other work, but he has never

lost touch

with our

Secretariat or with the work of the Constituent Assembly.

The members

of the staff have worked with efficiency and with devotion under our Deputy

Secretary

Shri Jugal Kishore Khanna. It is not always possible to see their work which is

done

removed from

the gaze of the Members of this Assembly but I am sure the tribute which Member

after Members

has paid to their efficiency and devotion to work is thoroughly deserved. Our

Reports

have done

their work in a way which will give credit to them and which has helped in the

preservation

of a record

of the proceedings of the Assembly which have been long and taxing. I must

mention the

translators

as also the Translation Committee

under the Chairmanship of Honourable Shir G. S. Gupta

who have had

a hard job in finding Hindi equivalents for English terms used in the

Constitution. They

are just now

engaged in helping a Committee of Linguistic Experts in evolving a vocabulary

which will

be acceptable

to all other languages as equivalents to English words used in the Constitution

and in

law. The Watch

and Ward officers, and the Police and last though not least the Marshall have

all

performed

their duties to our satisfaction. (Cheers)

Comments

Post a Comment